Tech analysis: What’s behind F1’s 2021 engine row?

But if there had been any hopes of a smooth introduction for what initially sounded like a subtle change to the current power units, they were quickly dashed.

Less than 48 hours after the meeting with teams and manufacturers, Renault and Mercedes voiced fears of an unnecessary arms race, while Ferrari threatened to quit F1 completely.

But why has an idea to solidify the FIA and FOM's vision for the sport, reduce complexity, lower the barrier for entry and put more control back in the drivers' hands caused such controversy?

Clean sheet of paper

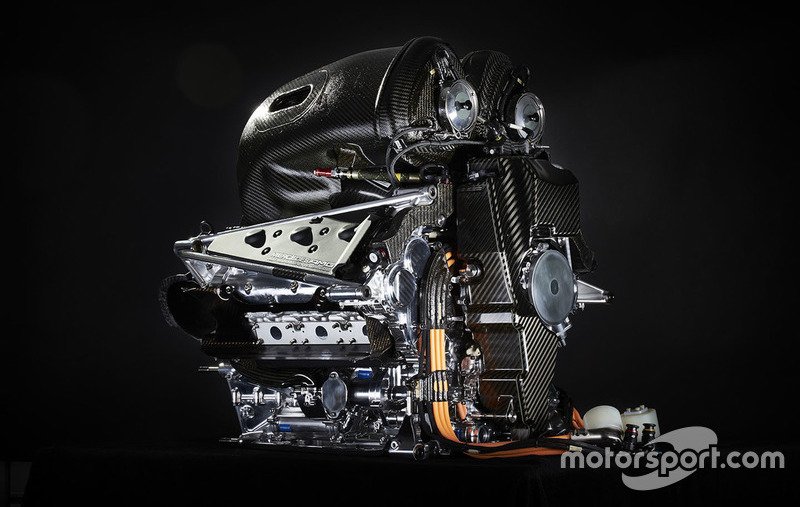

Having detailed knowledge of the development path required for the current engines, Renault and Mercedes are under no illusions that what has been proposed is not a minor tweak – it means an all-new power unit for 2021.

The V6 turbocharged architecture proposed gives the appearance of a like-for-like change with little to do in terms of redevelopment.

However, both manufacturers disagree and know that while they cannot unlearn the lessons of the hybrid era, they will undoubtedly be starting from a blank piece of paper when designing what has been proposed.

Thermal efficiency and intricate combustion processes that have been a hallmark of the hybrid era will be further complicated by a need to increase the fuel-flow characteristics and match the new rev limit profile.

Meanwhile, the loss of the MGU-H will require a rethink on the size and performance window of the turbocharger, as with the MGU-K reverting to a 'boost on demand' overall, power is already down 120kw (160bhp) all things being equal.

Having already stuck their head above the parapet, the current engine suppliers also suggested that the proposals are heavily weighted toward any new manufacturer wishing to enter the sport - while those already participating will be forced to run parallel development programmes in the next three years, as they develop the current power units and design entirely new ones for 2021.

As an alternative, bridging solutions for the current power unit have been offered, such as a relaxation of the fuel-flow limit and less restrictions on the fuel quantity that is carried, both of which are development barriers for manufacturers wanting to join the fray.

Not all is bad

Despite the concerns about costs, it is fair to say that the current manufacturers are not unhappy with all the ideas that have been put forward. Indeed, some proposals - like lifting the revs to improve the noise - have complete backing.

Manufacturers have also been clear in their opposition to a return to a larger engine displacement in recent months. Under the new roadmap, a 1.6 litre V6 ICE and single turbocharger will remain, which should in theory limit the development costs needed for the future.

Noise, much to fans' and the promoters' approval, will be higher, as a 3,000rpm increase in revs and the removal of the much maligned MGU-H, which naturally quells the turbocharger as it recovers energy from it, will change the engine's pitch.

The plans also include having just a kinetic motor generator, meaning F1 can return to a KERS-style boost deployed by the driver, rather than being preordained as part of an algorithm that F1 currently has.

There will also be cost reduction through a standardised energy store and control electronics, which will undoubtedly go some way to ensuring the likes of Aston Martin, Porsche, Cosworth and Ilmor can at least seriously consider an entry.

It is most likely hoped that the standardisation of some parts and the simplification of others will also have a positive impact on the reliability of the new units, further limiting the issues and penalties faced by some of the current manufacturers.

The bad news

From a technological point of view, though, the plan marks a move away from the super high-tech push that F1 had adopted since the turbo hybrid era came into force. It also means less separation between the car makers on their own engine identity, thanks to the increase in standard parts.

There have also be questions raised about whether a change is needed at all, for power convergence appears to be happening and the reliability niggles that have marred recent seasons will certainly improve over the next two years.

The KERS-style boost the FIA and Liberty wish to introduce may also become irrelevant if the driver is simply tasked with deploying energy out of each corner to overcome the turbo lag that's more or less guaranteed, given there is no MGU-H to help keep the turbocharger spooled up.

Then there is the issue of weight, something that should be a major consideration when framing these new regulations. F1 cars are already heavier than they have ever been, and that's before the Halo is added from 2018 onwards. Extra weight means more mass to accelerate.

The outline put forward does not openly take the weight issue into account, aside from the removal of the MGU-H.

But if you have to add a larger energy store to achieve KERS deployment targets, and increase the ICE's bulk to achieve the increased horsepower necessary, then we may not be better off at all in terms of laptime.

What is the solution?

Perhaps the answer lies somewhere between what has been proposed and what the manufacturers want.

Some rule tweaks could prove popular and tick most of the boxes for those concerned, allowing a retention of the current power units, with a gradual roadmap toward 2021 that also encourages others manufacturers to join the series.

An answer could include:

- An increase in the fuel mass flow and the removal of the calculation below 10,500rpm that artificially limits revs to around 12,000rpm, allowing the manufacturers to rev to the currently unachievable hard limit of 15,000rpm - improving performance and noise.

- Giving more freedom in regard to the amount of fuel that can be carried, allowing more varied strategy decisions both before and during a race.

- KERS overboost - Energy store capacity increased to 6mj to allow for a driver-deployable boost of 120kw (160bhp) on top of existing MGU-K delivery.

- An entirely standardised ERS and turbo - including MGU-H, MGU-K, energy store and control electronics - reducing unreliability and perceived complexity, and allowing incoming manufacturers the opportunity to focus on just the ICE.

Such changes should successfully address the identified issues of cost, noise, reliability, performance and barrier for entry for new manufacturers, whilst maintaining a common goal with those already involved.

Related News